MAY 2019

by Leslie Herd, M1

Congrats Grads

by Iqra Qureshi (M3)

Today you’re like a tree that gives fruit to whoever comes by,

but they wouldn’t have recognized you back when you were about to wither away

and you needed to be nourished with kindness and wisdom.

Challenge is your fuel; spoon-feeding is your downfall.

Don’t spoon-feed me; it defeats the purpose.

Give me the tools of your wisdom and toss me back into the wards.

I made it to these waters, and I’ll figure out how to swim.

Fast-forward:

You’re the kind of doctor who puts people at ease when you walk into the room.

You’re the kind who inspires people and makes them believe anything is possible.

You’re the kind whose busy clinic they’d take a road trip for:

the kind who fixes what needs fixing and heals those who need healing;

who celebrates with people on some days,

and on others, helps carry them through the darkness only they can see.

Your story is written into the way you are and the way you do things;

all the words you can find couldn’t capture what the people who’ve known you can read.

The courage and lessons have stayed, and the rest is buried

under countless memories that you don’t remember forgetting.

This journey has carried with it the pain of healing and growth, not the pain of suffering.

It has ingrained in you the ability to stand on your own two feet:

to see in the dark, to build your own contentment and take others with you,

to value people, to work hard and have faith, and to value yourself

even after all the mistakes you made before finally figuring it out.

Then, one day, you realize you made whoever risked putting their trust in you proud,

and that your success belongs to the people who refused to give up on you.

They gave you direction, and you put in the work.

Now you have the skills to serve those who need them;

they can be sure that they’re in good hands.

An Argument for the Humanities

by Bailey Baker, M1

The humanities are frequently viewed as a subject within itself; it is an institution with no practical relevance in the scientific realm. However, as we progress through our studies, we may come to witness how much there is to learn from the fine arts. When we look at the world refracted through art, we are able to see the human experience through the eyes of individuals who are often different from ourselves in their gender, age, race, education level, religion, or sexual orientation. Further, it is sometimes necessary to seek out protagonists who diverge from our beliefs and be willing to empathize with their views, choices, and hardships. The careful exploration of novels and artwork with these characteristics has the potential to open our vision to a wide synthesis of life, and it may teach us to extend our sympathies and cultivate a sense of compassion despite obstacles that may be faced. Becoming an effective physician involves empathetic judgement; however, the complexity of life can make these decisions challenging. By exercising compassion, clinical objectivity may work hand in hand with empathy, and the conditions for healing are maximized.

Through indulging in the arts, we may witness a distinct improvement in our thinking skills and problem-solving abilities. We should take advantage of these academic byproducts through applying them to our preliminary work in the basic sciences and capitalize on their potential to change the way we view medicine. Although diagnosis and treatments can be simple at times, there will always be an occasion that will challenge our aptitude and intelligence. In these cases, most will agree that lateral thinking, or “thinking outside the box,” may bring a much-needed remedy. However, you don’t always have to think outside the box if your box is big and rich enough in the first place, and that is where the value of the humanities makes its voice heard.

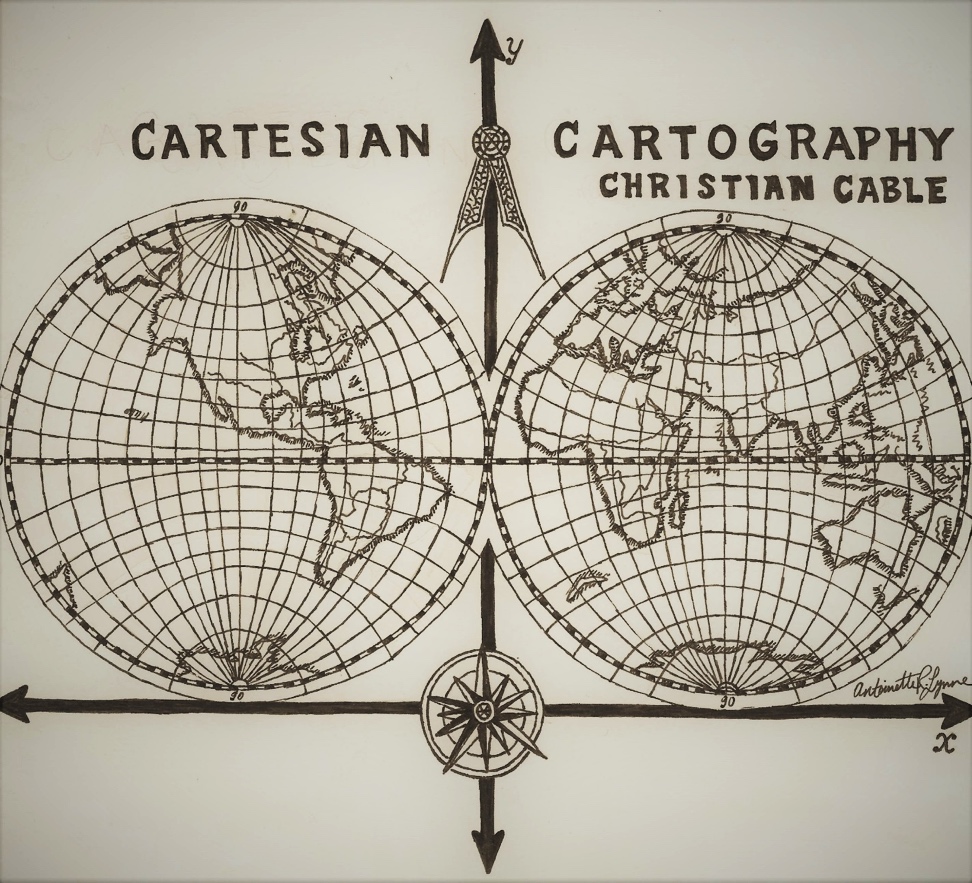

Cartesian Cartography

by Christian Cable, MD, MHPE, Clinical Professor of Medicine

Rene Descartes had an unusually expansive mind. In mathematics, he bridged geometry and algebra with the Cartesian coordinate system, which bears his name. In philosophy, he questioned his own existence and famously answered: Dubito, ergo cogito, ergo sum; I doubt, so I think, so I am.

Cartography is the study of maps. In Boy Scouts, I learned that a map is more important than a compass for navigation. So, Cartesian Cartography is my attempt to organize the thoughts and ideas that are important to me with an alliterative title. Let’s discuss the one that means most to me:

On the y-axis is love in increasing amount. Perhaps negative love is hate; more probably it is apathy. On the x-axis is like in increasing amount. Negative like is dislike. So, think about the different quadrants. They are numbered I-IV from upper right clockwise. I hope that your deepest life partnerships reside in quadrant I. Approaching twenty-five years of marriage with my wife Jill, I enjoy her company and find her likeable.

Before unpacking love, move to quadrant IV. Do you have family members you dislike? Tolstoy claimed that all happy families are alike, while unhappy families are unhappy in their own ways. Unless your family is peculiarly small, we all have members we dislike, yet love. So, what do we mean by love—a famously slippery word?

An ancient letter describes love with two adjectives: patient and kind. What a miserable list. This suggests that love is more of a choice than like is, and that patience is required. Keep your own counsel on quadrants II and III, and join me in a desire to recognize and move as many relationships as possible into the upper half.

I Am Feeling Rattled

by Cindy Thaung, M1

Medicine is the Ultimate Love-Hate Relationship

Anonymous

I hate taking tests.

I hate the pressure.

I hate putting studying first.

I hate how time-consuming this profession is.

I hate being away from my family.

I hate never feeling good enough.

I hate learning all of the details.

AND YET…

I love patients.

I love making a diagnosis.

I love the intimacy of listening to a patient’s heart.

I love serving others.

I love the feeling of getting it right.

I love realizing how amazing the human body is.

I love the brain and all of its neurotransmitters.

I love discovering and unveiling a patient’s story.

I love the complexity, even when it’s overwhelming.

I love explaining labs to patients.

I love feeling like I helped even in a minor way.

I love being there in the most difficult times.

Despite this dichotomy, the love for medicine keeps us going.

Heart & Skull

by Dani Shahin, M1

A Simple Question

by Sara Yasrebi, M1

Medical students are often told horror stories of physicians who have lost their empathy and compassion and the dangers that follow. We are told by friends and family that many doctors seem stoic; it is as if they’re only in it for the money. What we mostly warned of is that in the midst of our overwhelming studies we forget who we do this for—the patient. I never thought I would be subject to this. However, as I left my White Coat Experience last month, I felt not just joy and gratitude, but shame that I did not realize the true magnitude of the opportunity I was given before entering Ms. Jane Doe’s room.

Within the first minute of our conversation, Jane and I immediately clicked. Her first question to me was the classic, “What kind of physician do you want to be?” I responded by saying that I wasn’t sure, but I knew I wanted to do something in women’s health. She beamed as her face seemed to illuminate with delight. Almost immediately, Jane poured out her life story and confided in me that she was born with an extremely rare condition. Knowing that I was a medical student, she seemed to expect an answer along the lines of, “Wow, how interesting!” Instead, I held her hand and replied, “That must be very difficult for you. Would you like to tell me more about your experience?” Her eyes glistened as she responded and said how much she appreciated my empathy, but it was not the most difficult event in her life.

She continued by telling me that she had to undergo reconstructive surgery for her condition and had since lived an almost normal life. I was in awe at her experience—she had taught all over the world. However, one experience transformed her life and forever affected every aspect of her being. While working overseas, she unknowingly contracted HIV. When she returned to the United States and got her diagnosis, she fell into a depression. This was made worse by the poor reaction of her physician, who shamed her into silence about her diagnosis, even though it was undetectable HIV. She then went on to reveal more discriminatory stories, like this past July, when her dentist refused to prep her because he thought that she was a risk to his office. I was astonished by what Jane had endured and the horrible treatment she received from medical professionals. Her voice almost broke when she admitted that people were afraid to hold her hand.

It was at this point that I reached over and took both her hands in mine. I was not quite sure what to say, but this seemed to communicate more than words could. Jane and I were overcome with emotion—her needing to vent this anger, and my absorbing what had happened to this woman. With her hands still in mine, I told her that both she and her story were incredibly powerful. What struck me was that this conversation began with the simple question—What kind of doctor do you want to be?— and ended with both of us being open to each other and feeling less alone.

As I obtained Jane’s medical history, I realized how difficult it was at times to be mindful of her rare condition. We are instructed to take a complete medical history. I found myself beginning to ask certain questions but having to divert quickly to not make her feel uncomfortable or ignore her diagnosis. It seemed so easy to practice on friends who have few surprises or variabilities in their medical history. Practicing on someone whom I had just met, with conditions I was not familiar with, was completely different .

I have thought about Jane often. I entered the room expecting a generic rundown of her medical history and a simple review of systems. It wasn’t until after I left that I realized—nothing is generic. If you express empathy, establish trust, and ask the right questions, every patient is unique with their own story. Every patient can transform and teach you more than you could ever learn in a classroom. This experience taught me to never take any patient, other person, or experience for granted. Jane was my first patient and has changed the way I will approach every patient to come.

Enjoy Every Moment As It Comes

by Xin Wu, MD

Imagine You Are Alive in 2000 BC…

by Matt David, M1

The continuing tradition of attributing patients' physical ailments to non-physical entities goes back thousands of years, as seen in ancient Mesopotamian writings on epileptic seizures caused by deities. Here we see Mesopotamian deities on a Sumerian cylinder seal, c. 2300 BC, in the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York.

Courtesy of the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Sourced from Encyclopædia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ea/media/175484/5315

Imagine you are alive in 2000 BC. Let’s call you Emi–your mom and dad named you after an Akkadian ruler from the 22nd century BC. Since your birth you’ve lived in the countryside on a farm, along with your 4 brothers and 2 sisters. You have recently started having “spells” in which you fall over unexpectedly, only to wake up a few minutes later feeling weak and confused. Your parents and friends tell you that when you fall over, your body arches, twists, and goes into spasms.

You’ve probably already figured out what your character has in this imaginary scenario: epilepsy. The earliest description of epilepsy hails from over 4,000 years ago–a Mesopotamian document in the Akkadian language. In it, we find out how your family might have regarded your recent onset of seizures:

“[H]is neck turns left, his hands and feet are tense… [he has no] consciousness… antasubbû— the hand of sin”

Your parents call the exorcist, who informs them that you have been cursed by the Moon god. For the rest of your life, in addition to living with the terrifying knowledge that you could have another “spell” and collapse unexpectedly, you are shunned by your community. You never get married, your friends are too nervous to be around someone cursed with antasubbû.

How different would your life have been, had your family simply known what we now know: diseases, including those of the mind, have physical causes. For a person trained in the sciences, it is possible to take this for granted…But it is so, so important to nottake this for granted. A substantial number of our patients and their families still live with the same knowledge of the root causes of disease that humans had in antiquity–probably more than most of us are aware.

--

The realization of the physical reality of diseases is one of the greatest gifts mankind has ever received. We no longer have to fear the wrath of capricious malevolence, because every disease has an answer that is physical. We no longer need to let those who suffer from maladies like depression add onto their suffering the pains of alienation. We no longer have to leave those with chronic pain or fatigue syndromes wonder what they might have done wrong to deserve their illness. These patients have done nothing wrong, and there shouldn’t be one more day added to the millennia-long history of misplaced fear, judgment, and suspicion. The cells in their bodies, the proteins and ions and electrical activity between them, these are the actors on the stage of life, and it is the interaction of this system with the environment that is responsible for what the patient experiences.

Many diseases may have complex etiologies that are not immediately apparent to the science of medicine. The takeaway is not that we know all the answers, but that with inherently physical diseases, those answersare knowable. We have a destination in mind: a comprehensive physical model of the human body that explains all of human illness.

Despite all the headway that has been made, old habits die hard. Just as people with epilepsy were once called demon-possessed, and depressed people were accused of lacking faith, many patients with a variety of mental and physical health concerns are still often blamed for their illnesses. More Americans believe in demon-possession and exorcism than reject it, and entire swaths of the population still blame patients as if it is their own supernatural shortcomings that are to blame. Websites that offer belief-based advice still teach patients that depression often has entirely non-physical causes and go on advising patients to seek non-physical solutions. If the patients do not reach a resolution for their condition through these approaches, they are then dropped back into the cycle of blame.

Navigating this belief spectrum in our patient populations will certainly be a life-long learning experience. Let’s just not forget that every patient who learns of the physicalparameters causing their suffering has received a gift akin to time travel itself: They have taken a ship from 2,000 BC to the present.

Finally, let’s not forget the words of Hippocrates… He was the father of medicine for his insights into the patient-physician relationship, the author of an oath that we all recite. He powerfully delivered the insight that disease had fundamentally physical causes, thousands of years before science would be able to answer most medical questions. He had more than a few strong words for those who attributed mental illness to magical causes:

The fact is that the cause of this affection [epilepsy], as of the more serious diseases generally, is the brain…My own view is that those who first attributed a sacred character to this malady were like the magicians, purifiers, charlatans and quacks of our own day, men who claim great piety and superior knowledge. Being at a loss, and having no treatment which would help, they concealed and sheltered themselves behind superstition, and called this illness sacred, in order that their utter ignorance might not be manifest” -Hippocrates, 400 BC

--

For years, epileptic patients were a mystery to their families and physicians. Those living with epilepsy have lived within the reality of just how easily the complexity of human health could hide the fundamentally physical nature of disease. After suffering the pain and alienation of carrying a disease with poorly understood causes, the drug phenytoin was introduced about 80 years ago, delivering significant resolution for many patients. Since then, medical and pharmaceutical approaches have provided relief to about 2 out of 3 patients. The remaining third of patients have lived with the ongoing uncertainty of unresolved epilepsy. Just this past year, researchers at the TAMHSC Department of Molecular and Cellular Medicine published results in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggesting a possible cell-based therapy for patients who don’t respond to anti-epileptic drugs. After more than 4,000 years of documented struggles trying to understand this condition, we may finally have the opportunity for each epileptic patient to get the answers that every patient deserves – and an opportunity to experience life as it should be.

Interview with Dr. Julian Leibowitz

by Brianna Basinger, M1

Dr. Julian Leibowitz is the director of the MD/PhD program at the Texas A&M College of Medicine. He received his MD and PhD at Albert Einstein College of Medicine. His current research involves the study of coronavirus replication for the prevention and treatment of diseases such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).

Dr. Leibowitz and lab members. Photo courtesy of Dr. Leibowitz

What led you to choose the MD/PhD program instead of the traditional MD track? I always knew I wanted to study science since around age nine. I always liked to take things apart. I was good at biology and chemistry, and I was really interested in human biology. I also liked helping people. I’m not sure specifically how I found out about the MD/PhD program, but I discovered it at a time when there were very few of them in the country. In New York, where I was from, there were only two programs. I just remember thinking that the program sounded very interesting.

What led you pursue a PhD in addition to an MD? From a young age, I was broadly well read. I started reading Scientific American in junior high school, so I guess you can say I’m your prototypical nerd. Or maybe more of a middle of the road nerd. There were others in the MD/PhD program at Einstein that were way nerdier than me and others less so.

What was the process of getting into an MD/PhD program like? When I applied, I was an alternate. Since the dropout rate was around 10%, I began my coursework as if I was on the MD/PhD track by taking a graduate biochemistry course with the MD/PhD students. At the beginning of my second year, I got in. The program was supported by an NIH grant. I can’t remember specifically how many people got in, but it was around 7 or 8 people each year.

How is the MD/PhD program different from the traditional MD program? They are very different. MD education is a mile wide and an inch deep. PhD training is two inches wide and a mile deep. By the end of a PhD education you will be the world’s expert on a specific topic. Most PhD students, by the midpoint of their training, want to focus on finishing and what they need to do to graduate. MD/PhD students don’t do that. They read more broadly. They think, sometimes, more extensively on how things are applied to patients.

Who should apply to an MD/PhD program? Someone who is not scared of commitment. Someone interested in research from undergrad or medical school. My goal is to turn out the next generation of physician scientists.

Is it OK for someone in the traditional MD program to not be interested in research? It’s OK to not be interested in research. Medicine is a noble calling. PhDs have more of the mindset of finding a problem and solving it, thus advancing the field.

What or who got you interested in the field that you currently research? I read a review article in the New England Journal of Medicine by Arthur Kornberg, a Nobel laureate for the enzymology of DNA synthesis. Kornberg received his medical degree and served in World War II. After the war, he wanted to cure cancer, so he studied DNA synthesis in mammalian cells. Kornberg wrote that mammalian cells were too complicated, and it took him 5 years to figure out that E. coli were also too complicated. So, Kornberg went to the smallest thing he could find with DNA, and that was a bacteriophage, phiX174. It has around 10 genes… That was something he could study. What I took away from that was to keep it simple. Before molecular cloning, studying the molecular biology of viruses was one of the few mammalian systems for doing molecular biology.

Dr. Leibowitz with students at the MD/PhD retreat. Photo courtesy of Dr. Leibowitz

What advice would you give to MD/PhD students? I worked with a freshly minted assistant professor. This was very high risk. Don’t forbid yourself from working with one, but you will not know how long it will take. Also, you can’t talk to other students [to see how working with the professor is]. Talk to a lot of faculty about their projects, talk to their current students, and don’t overthink choosing a PhD advisor. Use your best judgment about the projects and your intuition about the advisor to make a decision.

What advice would you give to MD students? The most valuable thing the dean of my medical school said was, “Welcome. You are all getting subscriptions to the New England Journal of Medicine. You are to read one article per week to learn how to think like a physician.” It was relatively painless (there were no tests on the material), but I was amazed by how much I could learn this way. Read.

How did you choose your specialty? I was undecided between internal medicine, infectious disease, and pediatric infectious disease. During my pediatrics clerkship I got sick a lot… I must have caught all the upper respiratory infections in the Bronx. There were a lot of sick kids, though, many with chronic disease. I just did not like dealing with the parents. It wasn’t until I became a parent that I realized I was seeing parents at their worst. Einstein has a strict antibiotic policy. Parents would bring their child in with a cold and insist they needed antibiotics. I found it hard to work with those parents.

An infectious disease specialist on my PhD advisory committee, Dr. Matthew Scharff, recommended that I specialize in pathology. He said this because pathologists had more control over their time and would always have access to a lab. Matt was way smarter than I was, so I took his advice.

I chose pathology even though I never took it as an elective. My wife was very happy because there was almost no evening call time.

What do you think the future of medicine looks like? I think there will be two competing forces that will shape future medicine. The first is the push for precision medicine. I think we will see more of human genome sequencing and precise therapy for individuals. For example, I can see cancer tumor sequencing or tweaking diabetic insulin receptor promoters as treatment in the future. The second force is the problem of cost. We need cost to be less or have costs distributed differently.

What do you do outside of work? I read a lot—mainly history and biographies. I like gardening because my wife likes to garden, and I get to eat what she grows. I really like BBQing. It involves splitting wood and fire and, to me, it’s chemistry. It is an experiment to find the best … and I get to eat the results.

Brianna Basinger, Copy Editor

Riti Kotamarti, Copy Editor

Alexandra Powell, Copy Editor

Steven Le, Social Media Manager

Luke Mascarenhas, Chairman of the Board

Andrew Haskell, CT(ASCP)CM, Managing and Acquisition Editor

Michelle Won, Design Editor

submit to us!

Share your work with the Texas A&M medical school

community. Please email us at COM-synapse@tamhsc.edu to submit work, make suggestions, or ask questions. We

are looking forward to hearing from you!

thank you:

A special thanks to...

Dr. Karen Wakefield for being our faculty editor,

Dr. Barbara Gastel for serving as editorial mentor,

and Dr. Gül Russell for providing support and encouragement.

The Synapse is sponsored by the Department of Humanities in Medicine at the Texas A&M University College of Medicine.