Motivation

By Erin Lincoln, M1

“I don’t know how you do it.”

I just do.

And it isn’t about how—how is easy. I wake up, do what needs to be done, and go to bed. Then I do it again. And again.

It’s about why—why I get up, pack lunches, take her to school, study, go to class, study, go to lab, pick her up, eat dinner with her, wash hair, brush teeth, read a story, kiss goodnight, and then study more.

It’s about why the answer to “just one more story, Mom,” is, “I’m sorry sweetie, I have to go study.”

I do it because I have dreamt of this since I was four, and I would be a hypocrite to give up my dreams then tell her to reach for hers.

I do it because I want her to know that a passion is worth pursuing, even if the path is long and winding.

I do it because she needs to see sacrifice and discipline.

I do it because she needs to know that hard work is worth it.

I do it because it’s okay to be Mom AND… not OR.

I do it because I want her to know that being a woman and being anything else are not mutually exclusive.

I do it because I want her to see—and feel—that life isn’t always easy, and that hard isn’t bad.

I do it because she looks at me and says, “I want to be just like you, Mommy.”

How do I do it with her?

I couldn’t do it without her.

My First Procedure

By Krystha Cantu, M3

In the ER I paced through, unacknowledged

A buzzing fly in a white coat

Room D53, my destination

Inside, a peripherally wasting woman

Vanishing like a receding shoreline of thinning flesh

I was answered with soft breadcrumbs for words

“Yes..”

“No..”

“Sometimes..”

A long stare at the hospital floor with inspiratory whooping coughs

Each cough a millisecond of paused time with which to scramble for thoughts

A differential diagnosis

I squirmed around the cables of oxygen, beeping monitors punctuating my uselessness

“Excuse me I need to check her blood glucose”

A smothering of bodies, a whirlwind of bustling intervention

My notes, a bouquet of inadequacy, were a losing deck of cards

The lunacy of the ER is astringent

A violent retching sound from the next room was

a faint apocalyptic humming in the background

I am drowning in my own self flagellation

To let her sleep? Do I go on?

Photo by Cody Cobb, M2, Click to Enlarge

At last

her feet

The diabetic mandate

The cornerstone of physical dance between this patient and clinician

revealed two gaping ulcerations,

weeping, pink, neglected like melting candles..

My heart stopped

What could I do?

I felt them much more than she did

“I’d die for a tuna sandwich with milk”

She muttered

One more thing I couldn't guarantee

The next thing I know

Nurse shuffles in with tuna and pudding in hand

Her osteoarthritic fingers writhed with anticipation but

were weighted with an invisible molasses of pain

“Can I make the sandwich for you?”

“Yes…Glory be…” she smiled at me for the first time

Then tuna became my therapeutic intervention

Three years of medical school to feed one precious mouth

but no expanse of clinical apprenticeship can define how much it fed me too

My Voice

By Cara Gray, M2

I have always had a voice. No injustice has ever occurred without my opinion on it being known. Chalk it up to the fact that I was raised by a single mother who always taught me to be independent and to rely on no one but myself. Whether it be in response to an unfair judgment made on me or a friend being treated unkindly without reason, my voice will be heard. Some people in my life rely on my voice to be their own. I have always had a voice.

I stared hazily into the room. Where am I? What is wrong with me? How long have I been here? These were the first of many questions I had, but I did not speak them aloud. Besides these first questions, I do not recall much from the first day, or the following days. I believed I was once taken outside to get fresh air. I could see the awning over my head and hear the wind outside and hear the insects making their voices heard. Another day, I thought I was in my high school’s nurse’s office. I also remember thinking I was on a cruise ship surrounded by marine biologists who were leaving the room to go onto the deck and take samples from the water. I later learned that none of these events transpired. I had remained in the same bed in the same corner for the last few weeks, and I had never been moved.

There was one vivid memory I have which was true, and it was the first time I acknowledged I could not speak. My sister was visiting and using some butchered version of sign language, I asked her where I was. I will never forget the look of shock on her face, which was probably because I had been conscious for two days and was just now asking the question. As she reluctantly explained that I was in Methodist Hospital’s Intensive Care Unit, I focused on how I asked her the question. I did not ask her where I was with words. I was confused as to why I had no voice.

I suddenly remembered the events that had occurred over two weeks prior. I remembered the elephant I thought was sitting on my chest. I remembered being at my local hospital struggling to breathe. I remembered the two nurses running with my hospital bed down the hall to the ICU. I remembered turning to my mother and saying, “If they don’t do something soon, I am going to just stop.” I remembered feeling more exhausted than I had ever felt in my whole life. And then I remembered the tube. The tube that was now inside my trachea helping me breathe was the same tube that kept me from having a voice.

In the following days, there was so much I wanted to say. I wanted to ask when this tube would be taken out of my throat. I wanted to thank my mom for unselfishly staying at the hospital every night that I had been there. I wanted everyone to know how appreciative I was for them visiting. I wanted to know why I could not turn my head without coughing like crazy. I wanted to know what that torture device was that made so much noise, took all my air away, and made me sweat profusely. I wanted to ask when the doctor would be here. I wanted to ask the nurses to stop drinking Coke in front of me when I had not had a drink of anything in weeks. I wanted to tell the wife of the man in the bed next to me to be patient with him, because he thinks that the scribbles on that piece of paper make perfect sense. I wanted to yell at the nurse when she revealed that I could have been unconscious when having the NG tube inserted. I wanted to scream at her that pushing that tube down my nose and into my stomach while awake and alert was one of the worst pains I had ever felt. I wanted to thank my aunt for holding my hand through that experience. I wanted to tell my mom that I did not want to go to medical school anymore because the thought of having to ever step foot in a hospital again made me feel defeated. I had so much to say, but I had no voice.

People who want to become doctors do so because they want to help people in the greatest way imaginable. They want to heal people by using their knowledge, their diagnoses, their treatments, and in my case, their voice. I was saved by the voice of my pulmonologist. Dr. Moran was the third pulmonologist put on my case. I remember liking her immediately and being surprised by the fact that the doctor was coming by my bed so late on a Saturday. She asked me if she could run some tests to measure how well I could breathe. I had already agreed to the tracheotomy on Monday, but I had this glimmer of hope because I could see it in her eyes: she wanted to take out my tube. She told me that she believed the ventilator was keeping me from breathing as well as she thought I could. “We’ll take it out tomorrow,” she said with a confident smile.

I was ecstatic, but my good mood lasted only a few hours, unfortunately. A respiratory therapist inadvertently suctioned me again that night and told the nurse directly in front of me that it was impossible for Dr. Moran to want to extubate me with the numbers seen on the ventilator. My hopes were shattered and I felt empty, so I was astonished when Dr. Moran walked into the ICU the next morning with a smile on her face. Even though the hospitalists on the floor questioned her judgment, she still insisted on removing my tube. She believed in me and defended me when I had no voice. She was my voice because she could see the determination in my eyes and knew I would do anything to have my voice again.

I was surrounded by doctors, nurses, and family when the time finally came. I was the interesting case in the ICU, and everyone wanted to be there to see my happy ending. The tube was removed and I was instructed to start coughing immediately as hard as I could. I remember that moment as if it were yesterday; the joy, pride, and relief I felt in that moment will always be a part of who I am.

I am incredibly appreciative of my encounter with acute respiratory distress syndrome that led to unexpected lung failure. One day, I am going to be a doctor. I know I was given this experience because it will help me to better serve patients in the future. Having been a patient without a voice, I beg you to stand up and speak for your patients. It may be difficult, but as a doctor, you need to advocate for every patient who enters your life and be their voice.

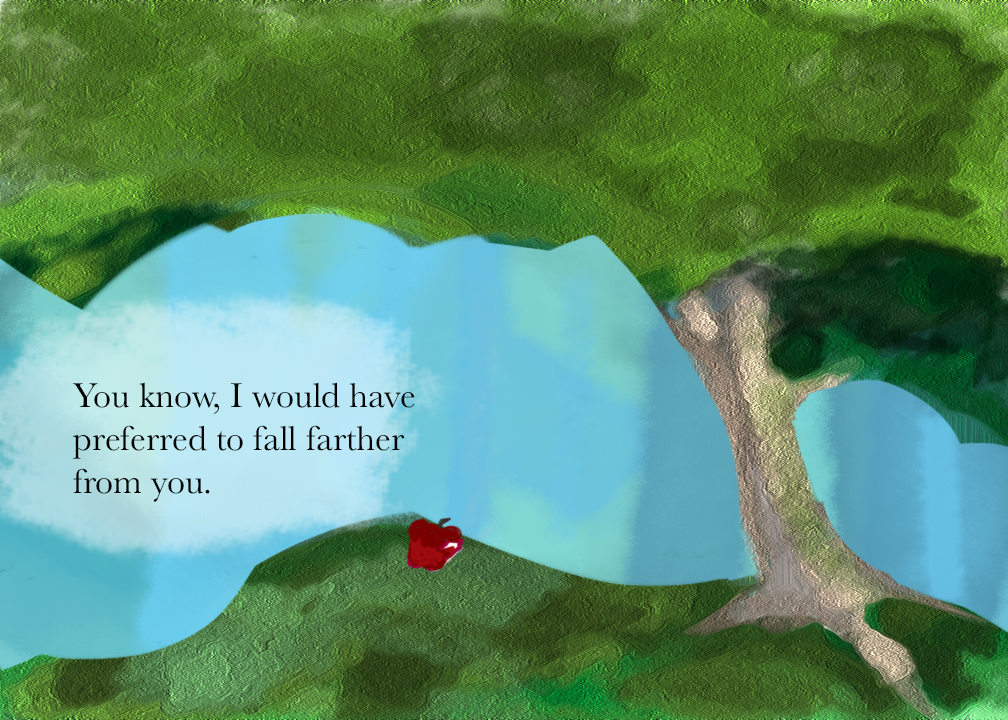

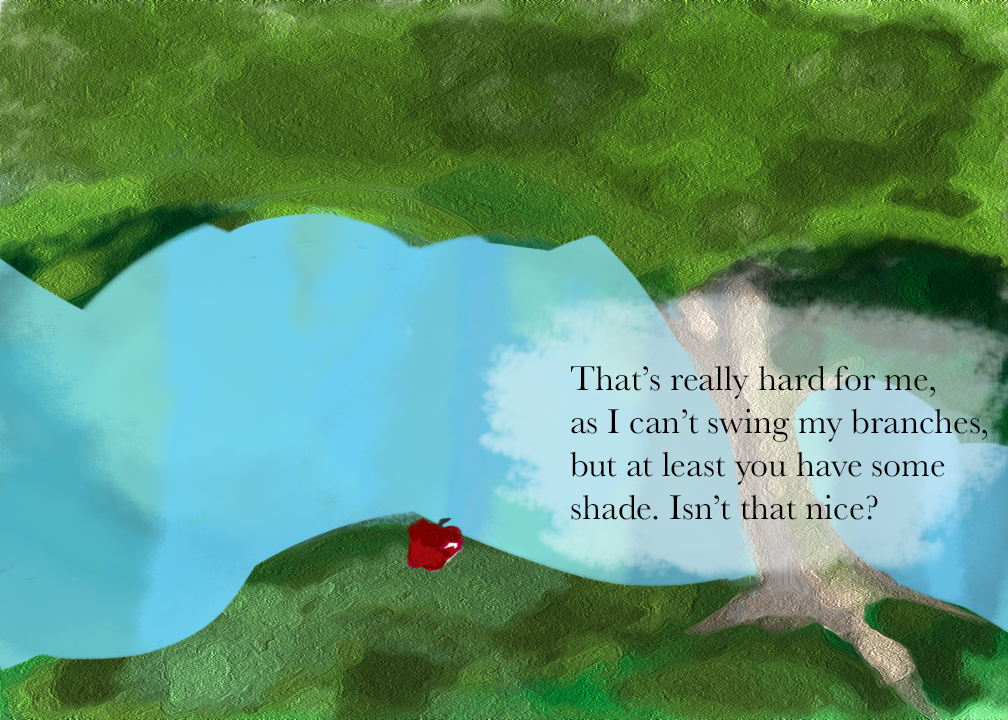

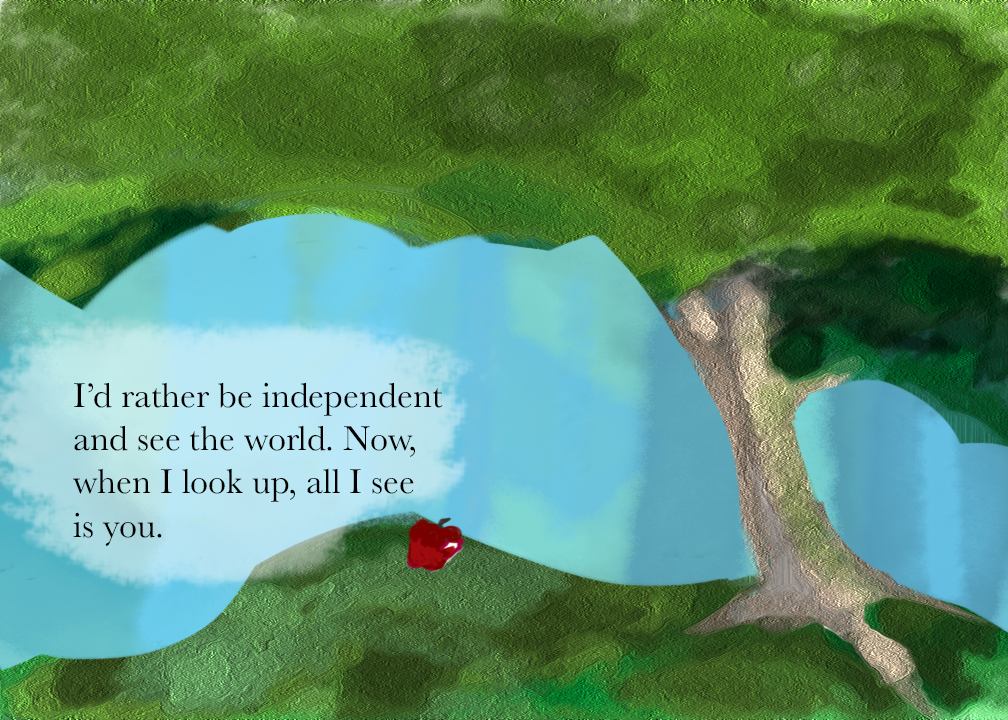

The Apple and the Tree

By Anand Jayanti, M2

Medical Humanities: A TAMHSC Alumnus's Perspective

The Synapse’s own Meherin Huque had a chance to talk to Dr. Hormuz Nicolwala, a College of Medicine alumnus who was involved in medical humanities and medical narratives while he was a student.

Meherin: When did you first start being involved in medical humanities and narratives?

Dr. Nicolwala: I always had an interest in medical humanities, even before I started medical school, but it was not until medical school that I physically started writing articles and contributing to medical magazines.

Meherin: How has your involvement progressed?

Dr. Nicolwala: I initially started out as a medical humanities writer for in-Training Medical Magazine where I honed my medical writing skills and where a lot of my initial publications were done. As a medical student at Texas A&M, I also took part in the Leadership in Medicine elective that was then run by Dr. Gastel. It was during that elective that I further honed my medical writing skills and interests, and subsequently worked my way up to student editor of in-Training Medical Magazine. I highly encourage medical students to be patient and develop their interests in medical writing and not write to just write.

Meherin: How has writing been helpful to you as a physician?

Dr. Nicolwala: Every time that we are privileged to interact with patients, be it a simple examination or even simply entering a patient’s room, we are fostering a sacred bond and relationship to respect, honor, and heal another person’s humanity beyond our own. I believe medical humanities empowers physicians to be great advocates for their patients and to serve their calling with humility and gratitude.

Meherin: What do you miss most about TAMHSC and Texas?

Dr. Nicolwala: Honestly, what I miss most about Texas is the people and the relationships I fostered while at TAMHSC. We all know medical school is tiring and is a test of one’s patience. However, along the journey you meet people that make the experience all the more better. You develop friendships that will live with you for your entire lifetime and it’s great! I highly encourage medical students to have their group of friends... and study with them as much as possible at HPEB (laughs).

Dr. Nicolwala is currently a first year pediatrics resident at the Children’s Hospital of West Virginia.

Healthy Gardens

By Cullen Soares, M2

This is the third year of the Texas A&M Health Science Center Healthy Gardens club on the Bryan campus. We are open to all students from the Health Science Center, but our members are predominantly nursing and medical students. This semester, the officers were maintaining the garden that had grown throughout the summer, which included okra, tomatoes, zucchini, peppers, watermelon, cantaloupe, basil, and eggplant. A few weeks ago, it was time to say goodbye to many of the old plants that had become unproductive. Members from our club got together to plant our winter garden. This garden contains many cold-hardy plants including broccoli, cauliflower, kale, spinach, collard greens, cabbage, leeks, onions, and brussels sprouts. We kept some summer plants that were still producing, namely peppers, eggplant, okra, and basil. We also have a herb bed which is productive year-round containing sage, rosemary, thyme, and mint. Members of our club are free to pick from our garden’s community beds. Additionally, members can reserve a bed space exclusively as their own to manage and enjoy. Recently, we appointed two new first-year medical students as class representatives for our club. As the school year progresses, we are looking forward to participating in community service projects that promote gardening and healthy lifestyles.

Fiestas Patrias

By Jose Garcia, M2

Fiestas Patrias is an annual festival in downtown Bryan that celebrates Mexican heritage in September. The festival is full of great food, drinks, vendors, and music. Hundreds of people, mainly Latinos, from the Bryan-College Station area show up for the festival, making it a prime opportunity for our organization, the Latino Medical Student Association (LMSA), to make an impact on this underserved part of our healthcare community.

The way we do our part in advancing healthcare in the Latino community at Fiestas Patrias is mainly through health education. This year we set up a booth with an anatomy mannequin, information on sugar and fat content of foods, presentations on arterial stents, and coloring books for the kids. Curious passersby stopped at our booth to ask about different diseases such as diabetes and hypertension, to play with our anatomy mannequin and learn about body parts, or to pick up a coloring book on hygiene. In addition, our volunteers gave out pamphlets and other materials on healthcare resources in the community to the people stopping by, all the while gaining experience in interacting with the Latino community.

Photo by Jessica Nguyen, M2

We could tell that the adults who stopped by our booth left with a bit more health knowledge than they came in with, at least in respect to sugar and fat content in common foods and the disease progression of atherosclerosis. The children were ecstatic when they received their free coloring book and when they got to play and learn with our anatomy mannequin. One little boy, in particular, came back several times just to rearrange and name the organs; certainly a future doctor in the making.

With our continued involvement at Fiestas Patrias, we at LMSA hope not only to educate the Latino community on their health, but also to inspire adults and children alike to take an interest in improving their health so that one day health disparities in the Latino community will be things of the past.

THANK YOU

To our amazing faculty mentors: Barbara Gastel, Mary Elizabeth Herring, Gül Russell, & AJ Stramaski

A special thank you to Barbara Gastel for helping with final edits!

Faculty Editor: Karen Wakefield

Submit To Us!

Share your work with the Texas A&M medical school community. Please email us at COM-synapse@tamhsc.edu to submit work, make suggestions, or ask questions. We are looking forward to hearing from you!